EARLY CONTACTS

Relations between the Chinese and the Filipinos predate Magellan’s arrival by many centuries. Barter trade from north to south of the Philippine islands saw the exchange of silk, porcelain, farm implements, ornaments with tortoise shells, swallows nests, mother of pearl, and other products.

Chinese ceramics, dating from the 10th to the 17th centuries, unearthed in the Philippines, stand testament to the intensive and extensive maritime trade between China and the Philippine islands. The CHING BAN LEE PORCELAIN GALLERY showcases these tradewares coming from kilns throughout Fujian Province spanning several centuries.

THE SPANISH PERIOD

THE PARIAN

When the Spaniards settled in the islands, more Chinese came, and served as the backbone of the Spanish colonial economy. Because of their growing numbers, the Spaniards both needed and feared them, which led to the persecution and harassment including large-scale massacres. The Chinese, or Sangley as the Spaniards called them, were separated into quarters called the Parian where they lived, worked, and made better lives for themselves as laborers, merchants and artisans.

COLONIAL CULTURE

Spanish colonial culture is intimately linked with the spread of Christianity. The Sangleys contributed largely in the building of churches, carving religious icons often decorating them with Chinese motifs, printing religious books and catechisms. The first three books in the Philippines were printed by Keng Yong of Binondo in 1593. Many Chinese in the Philippines also practiced religious syncretism, the unique product of Catholic and Buddhist intermarriage. Lorenzo Ruiz, the first Filipino saint, was born in Binondo to a Chinese father and a Filipino mother. He was canonized in October 1987 in Rome. Mother Ignacia del Espiritu Santo was also a Chinese mestiza.

LIFE AND ECONOMY IN THE 1800s

For the Chinese, this was a time of opportunity, innovation, and adaptation. Spain’s decision to develop the Philippines economically, its liberalized immigration policies, and the deteriorating economic and political situation in Fujian and elsewhere in South China encouraged a much greater overseas migration flow of Chinese than before.

A Chinese population of 5,000 to 6,000 in the early 19th century Philippines quickly expanded from the 1850s onward to around 100,000. A law in 1839 lifted the travel ban and allowed the Chinese to reside anywhere in the Philippines regardless of occupation. The Chinese thus created a network that linked international trade with local enterprise.

Major Chinese import-export merchants in Manila (and later in key trading cities like Iloilo and Cebu) were linked to their agents at various sites around the country. The major merchant, known at the time as a cabecilla, provided imported or other goods to his agents around the country. The agents distributed these regionally to local retailers, the sari-sari store.

Also known as the Bahay na Bato, the typical mestizo house – the area’s storekeeper keeps his sari-sari store and tool shed on the ground floor, and the family residence on the upper floor.

EMERGENCE OF THE CHINESE COMMUNITY

At the end of the 19th century, life became more difficult because of Spanish harassment and distrust. Hence, the Chinese started to form institutions for self-protection – school, hospital, cemetery, business groups. Pioneer businesses like China Bank, Destileria Limtuaco, Yutivo, Ma Mon Luk started to appear.

THE AMERICAN PERIOD

In the early 20th century, the American colonial government nationalized identities in the Philippines. The “mestizo” and “indio” ethnic classifications were subsumed under the classification “Filipino.” Under the new system, the “Chinese” became effectively an “alien” citizen. A mestizo whose father was classified as “Chinese” assumed the same classification of his father but could choose to become either “Chinese” or “Filipino” upon reaching the age of maturity. For pragmatic reasons, many chose to become “Filipino.” In time, Chinese mestizos became distanced from their “Chinese-ness” and more identified with their “Filipino-ness.”

The arrival of the Americans gave the Chinese more opportunities for growth. They distributed American goods all over the country, and procured cheap native products and raw materials for Western markets. In the darkest hour of the Japanese occupation, they fought side by side with Filipinos for freedom.

These economic adaptation and developments would blaze the trail for greater and more rapid growth during the American occupation.

THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION

On July 7, 1937 the Sino-Japanese War broke out in China with the infamous Lu Kou Chiao (Marco Polo Bridge) incident. The Chinese in the Philippines sympathized with war efforts in China and the entire community was mobilized to send aid to China and boycott Japanese goods. Community organizations moved as one to support China’s resistance to Japanese occupation.

Because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941, war was brought to the Philippines, an American territory. On the first day of war, all the Japanese in the Philippines were sent to internment camps.

As the Japanese took over businesses, factories became idle and the economy was subjected to severe financial strain. Many Chinese migrated to rural areas where Filipinos helped protect and conceal them in their own homes. When found out, however, these Chinese barrio residents were massacred.

The most infamous of these massacres was carried out on February 24, 1945 in San Pablo, Laguna. Around 6,000 Filipino and Chinese males between 15 and 50 were gathered, and the Chinese, 650 in all, were picked out. All were bayoneted and thrown into trenches that they themselves had dug. Several wounded survivors were taken to a local hospital, only to be killed the following day. Some of the badly wounded crawled to their homes with the help of Filipinos. In Los Baños, all the Chinese found in town were executed because of increased guerrilla activities in Laguna and the liberation of American war prisoners from the Los Baños internment camp.

Most anti-Japanese elements went underground to carry on the resistance movement. Many either cooperated with Filipinos and Americans or operated independently against Japanese forces. Some of the guerrilla units also helped in the orderly and peaceful evacuation of the residents whenever news of Japanese army roundups was received.

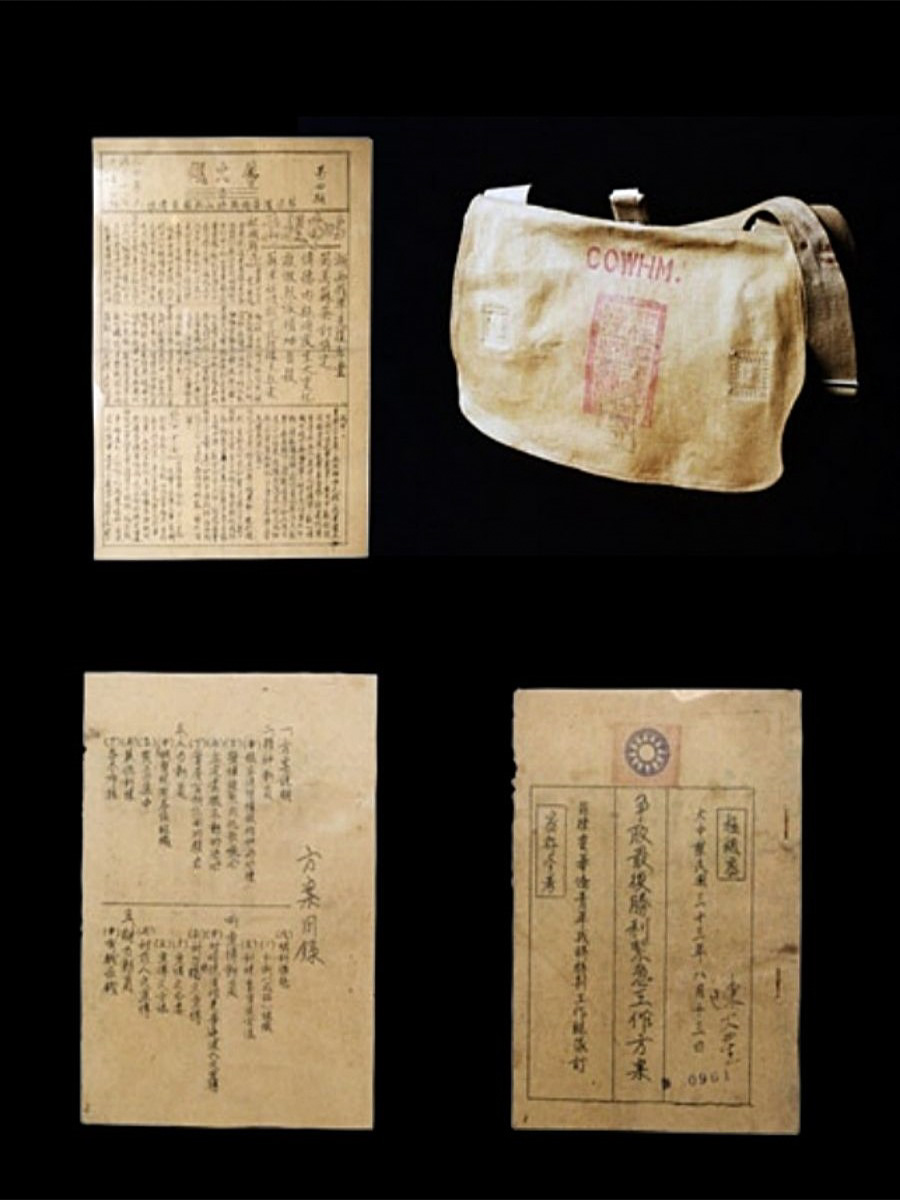

Among the most prominent underground guerrilla groups were the Chinese Overseas Wartime Hsuehkan Militia (COWHM 華僑戰時血幹團), the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese Guerilla Force (Wha Chi 菲律濱華僑抗日支隊), the Philippine Chinese Youth Wartime Special Services Corps (菲律濱華僑青年戰時特別工作總隊), the Philippine Chinese Volunteers (CVP 菲律濱華僑義勇軍), the United States-Chinese Volunteers in the Philippines (USCVP 美國-菲律濱華僑義勇, the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese and Anti-Puppets League (Kang Fan 菲律濱華僑抗日鋤奸義勇隊), and the Pek-kek 399th Squadron. With the exception of the pro-communist Wha Chi and Kang Fan guerrillas, the four other units were of Kuomintang political persuasion.

Like their Filipino counterparts, Chinese guerrillas conducted liquidation missions, sabotage, gathered military intelligence, and helped prisoners escape. They published several propaganda materials on the war efforts, gave information on the actual war situation, and exploited news on Japanese atrocities to promote patriotism. They earned the respect and gratitude of the Filipinos when they showed their readiness to sacrifice their lives to be freed from Japanese rule.

CONTEMPORARY

NATIONAL LEADERS OF CHINESE DESCENT

Only their names, and sometimes only their ancestry, are clues to the two worlds and the two cultures, which their families had straddled. The contemporary Tsinoys bearing the twin virtues of their heritage continue to enrich history and make a strong impact on all aspects of Philippine life.

TSINOYS IN NATION BUILDING

The modern-day Tsinoys, their industries and enterprises, outreach and development projects, civic consciousness and zeal in addressing Philippine concerns are products of this transformation.

Medical and relief missions, volunteer fire brigades, school-building projects, charity clinics, orphanages, farmers’ centers, agricultural ventures, consumer products and enterprises that have become household words, support the government’s poverty alleviation programs and highlight the Tsinoys contributions in nation-building efforts.

RELIGION

CHRISTIANITY FOR THE HEATHENS

The Spanish colonization of Manila was meant to be a stepping stone towards the evangelization of millions of heathens in China. Thus, the Dominican friars, especially those in Binondo Church, quickly learned the Chinese language from the Chinese. It was no accident that among the first three books printed in Manila in 1593, two were in Chinese and Spanish. Lorenzo Ruiz, our first Filipino Saint, was baptized in Binondo Church. His father was pure Chinese.

Mother Ignacia del Espiritu Santo, founder of the first Beaterio of the Virgin Mary was born to a Chinese father and an indio mother. Typical of the mestiza families in early Spanish occupation, both Lorenzo Ruiz and Mother Ignacia were raised as Malays by their Filipina mothers.

Most mestizos during the Spanish were raised Catholic, and also practiced some Chinese religious customs. Many mestizos grew up in households where local, Catholic, Hispanic, and Chinese customs were practiced together.

WHAT THE TSINOYS BELIEVE TODAY

In a pluralistic Philippine society, Catholic masses and Buddhist rites in one event is not an isolated practice.

For example, at the wake for former Philippine President Corazon Aquino at the Manila Cathedral in August 2009, a funeral mass officiated by His Eminence Cardinal Gaudencio Rosales was conducted side by side with a Buddhist service. Tsinoys of all ages performed the rite of Three Bows, showing great respect to the country’s beloved leader.

Is it Buddist? Taoist? It is important to distinguish Chinese religion as a broader category from either Buddhism or Taoism. Long before the latter two developed as religious traditions, there was already a Chinese religious sense that included the veneration of ancestors and divination.

Taoism has absorbed the Virgin Mary, Sto Nino, and many Buddhist bodhisattvas that they gave new names to. For example, in Chinese Buddhism, the formal name of Guanyin is Guan Shi Yin Pusa (观世音菩萨), but in Taoism or folk religion, she is simply Kwan Nim Ma 观音妈.

Over time, Chinese religion became the amalgamation of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, to the extent that some call it the Three Religions (三教) taken as one. Under Chinese religion are a plethora of folk practices which do not necessarily belong to any one of the three religions.

In the Philippines, Catholicism and Chinese religion can be practiced together: the (三教) can become (综合教) mixed religions.

FOOD

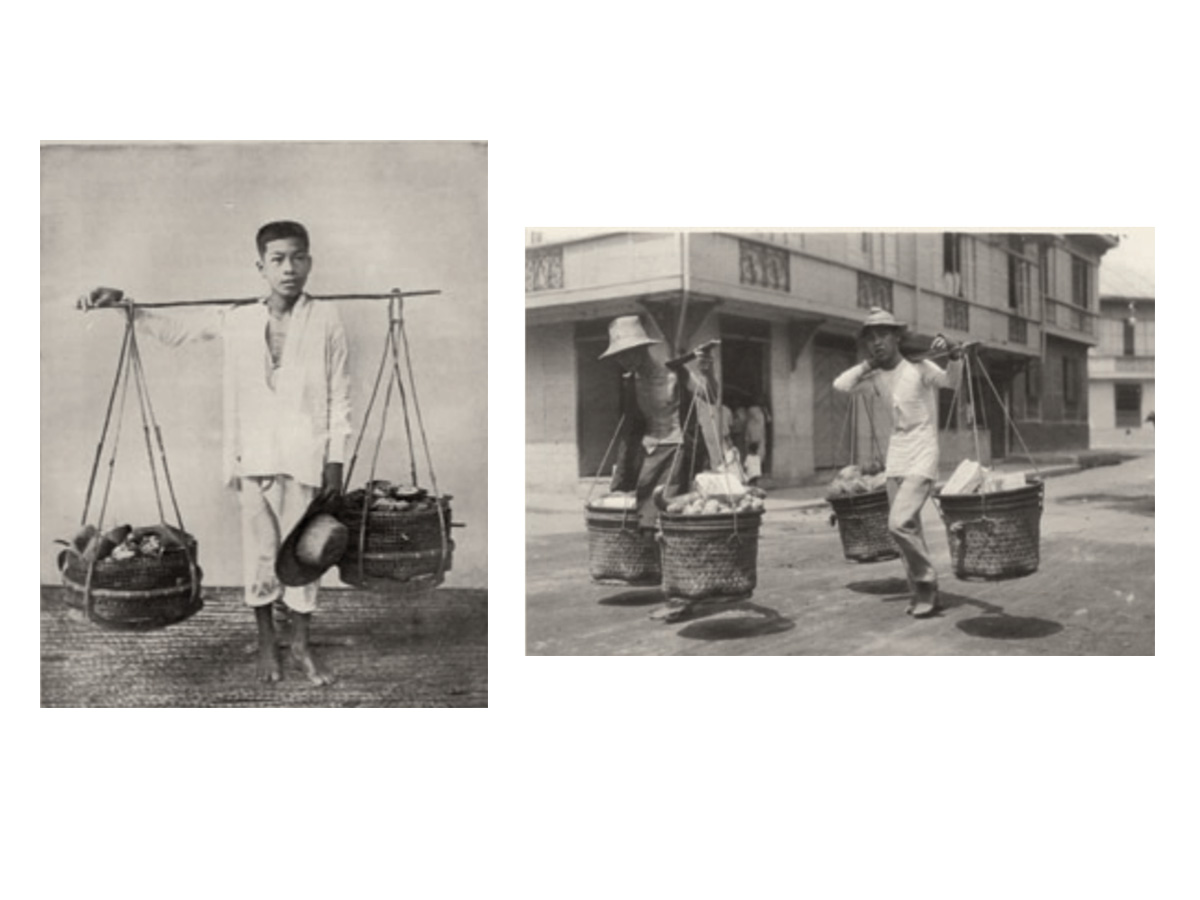

Comida China: Chinese food hawkers go anywhere with their baskets of food to serve factory laborers toward end of the 1700s century well into the early 1900s.

Pansit most probably refers to pian sit (便食) or fast food. The rich Philippine culture has transformed the pancit into myriad forms and tastes: molo, guisado, luglog, bato, palabok, Malabon, bihon, canton, habhab.

Sotanghon. The name comes from sua-tang-hun (山東粉), but the noodle itself does not come from Shandong Province, China. Older Chinese say there used to be a famous restaurant called Shandong Restaurant whose most popular dish was the sotanghun soup.

Lomi (硵麪). A thick stew-like broth seasoned with soy sauce. The name itself indicates the cooking process – lo (硵) is to stew or simmer slowly and mi (麪) the noodles.

Mami (肉麪). Originates from ba-mi, pork and noodles, popularized by Ma Mon Luk, a Cantonese schoolteacher who walked the streets peddling chicken noodle soup. The broth, which Ma made from fat native chickens, is continuously heated in a metal container with live coals underneath, while the noodles and utensils are in a large basket.

Bachoy. Ba-tsui (肉水). Literally meaning meat soup. If noodles are added and topped with ground chicharon, it becomes called La Paz bachoy, referring to its origin of La Paz, Iloilo.

Misua. Mni-snua (面线) is most popular ritual food among the Hokkien, served to relatives who came to visit for the first time. It is also served on other happy occasions like engagements, birthdays and weddings.

Lumpia (潤餅) Chinese food has evolved from its original Chinese Hokkien version or Cantonese version to a Filipinized version suited to the Filipino palate. Lumpia is one classic example of this evolution.

Goto gu to (牛肚) Cow tripe

Hibe hê-bí (蝦米) Dried salted shrimp

Humba Hong ba (烘肉) Highly spiced dish of pork

Kintsay Kim chay (芹菜) Flat leaf parsley

Wansoy Ien suy (葫荽) Cilantro

Pechay Peh tsai (白菜) Chinese cabbage

Toge Tau-geh (豆芽) Bean sprouts

Tokwa Tau-knua (豆乾) is a classic Asian white cube that is sliced or diced and added into local dishes. It can be fried or steamed as a whole, ready to be eaten as it is.

Toyo Tau-iu (豆油) or soy sauce is another Filipino staple that cannot leave the dining table.

Tausi (豆豉) black bean paste. The Japanese occupation and the immediate post-war years were difficult times of hunger and deprivation. This is the period when improvised Chinese sweet potato congee, tausi, and bamboo shoots became staples that helped tide people over hunger.

Taho Tau Hue (豆花) is a favorite sweet snack with tapioca balls and caramelized sugar. Vendors are distinguishable for bringing around two metal containers slung over shoulder poles.

Hopia is the Tagalog word derived from the Hokkien ho-pnia (好餅). In Fujian, China, hopia’s closest relative still looks like what it used to look like 100 years ago – bean paste inside a creamy dough skin. Early Philippine versions sold in Quiapo were made from green beans and flour or red beans and flour.

Tikoy Tni-ke (甜糕) sweet cake. It is the celebratory food item of choice during Chinese New Year. The sweetness and stickiness symbolize relationships between family members. The 甜糕is a traditional food item in Southern China as peasants and farmers celebrate the coming of the Spring. They would have just harvested their crop and food is aplenty.

Siopao (焼包) Siomai (焼賣). 90% of the Chinese in the Philippines come from Fujian Province or Hokkien. The rest are Cantonese who migrated to the Philippines in the early 1900s are. They brought to us these favorites.

Bigas (米)

Am (泔) Am

Biko (米糕) Bi-kō

Bilao (米漏) Bi-laò

Bilu-bilo (米糯) Bi-lō

Bithay (米篩) Bi-thay

Bitso (米棗) Bi-tsō

LANGUAGE

Through centuries of contact, Philippine languages, especially Tagalog, have inherited many Hokkien terms into the vernacular. Most popular of these words are those that deal with food. Language borrowings happen when words are used in daily life.

Ate Achi (阿姐) Elder sister

Ditse Dichi (二姐) Appellation for second elder sister.

Sanse Sanchi (三姐) Appellation for third elder sister.

Kuya Ke-ah (哥[仔]) Appellation for elder brother

Diko Di–kē (二哥) Appellation for second elder brother

Sanko San–kē (三哥) Appellation for third elder brother

Ingkong Angkong (公) Grandfather

Guya gu-ah (牛仔) Young cow/ water buffalo

Lawin lao-ieng (老鷹) Hawk

Bakya bak-ia (木屐) Wooden clogs

Hikaw hi-kao (耳鈎) Earrings

Bimpo bin-po (面布) Face towel

Kusot Ki-sut (鋸屑) Sawdust

Lithaw luey-thaw (犂頭) Plow head

Siyanse tsien-si (煎匙) Spatula

Susi so-si (鎖匙) Keys